Experiencing one or more of the symptoms detailed below does not necessarily indicate liver cancer. Many of these signs are more frequently attributed to other health issues. Nonetheless, it is crucial to consult a doctor if you notice any of these symptoms, to diagnose and treat any underlying cause if necessary. Although liver cancer symptoms typically appear in advanced stages, they can occasionally present earlier. Early medical consultation upon noticing these symptoms can lead to an earlier diagnosis, increasing the chance of successful treatment.

Symptoms of Liver Cancer

– Unintentional weight loss

– Loss of appetite

– Feeling excessively full after a small meal

– Nausea or vomiting

– An enlarged liver, noticeable as a fullness or mass under the right side of the ribcage

– An enlarged spleen, noticeable as a fullness under the left side of the ribcage

– Abdominal pain or discomfort near the right shoulder blade

– Abdominal swelling or fluid accumulation

– Itching

– Yellowing of the skin and eyes, known as jaundice

Additional symptoms may include fever, visible enlarged veins on the abdomen, and unusual bruising or bleeding.

Individuals with chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis might experience heightened discomfort or varying laboratory test results, such as changes in liver function tests or alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels.

Certain liver tumors produce hormones that affect other organs. These hormones can result in:

– Elevated calcium levels in the blood (hypercalcemia), potentially causing nausea, confusion, constipation, weakness, or muscle issues

– Low blood sugar levels (hypoglycemia), possibly leading to fatigue or fainting

– Breast enlargement (gynecomastia) and/or testicular shrinkage in men

– Increased red blood cell production (erythrocytosis), which may cause a flushed and red appearance

– Elevated cholesterol levels

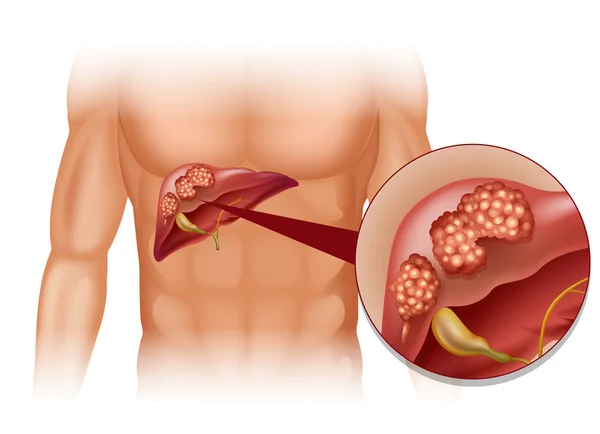

What Is Liver Cancer?

Liver cancer originates in the liver, a vital organ responsible for numerous critical functions. Cancer begins when cells grow uncontrollably.

The Liver’s Role

The liver is the largest internal organ, located under the right ribs, beneath the right lung, and divided into two lobes. Primarily composed of hepatocytes, it also contains cells lining the blood vessels and bile ducts. These ducts transport bile from the liver to the gallbladder or intestines. The liver performs essential functions such as:

– Processing and storing nutrients from the intestine; some nutrients must be metabolized in the liver for energy use or tissue repair.

– Producing clotting factors to prevent excessive bleeding from injuries.

– Secreting bile to aid in nutrient (particularly fat) absorption.

– Detoxifying the blood by breaking down alcohol, drugs, and waste products, which are then eliminated through urine and feces.

Various cell types in the liver can lead to different malignant (cancerous) and benign (non-cancerous) tumors, each with its own causes, treatments, and outcomes.

Primary Liver Cancer Types

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most prevalent liver cancer in adults, with two growth patterns:

1. A single tumor that enlarges and spreads only in advanced stages.

2. Multiple small cancer nodules throughout the liver, common in those with cirrhosis.

Subtypes of HCC generally do not impact treatment or prognosis, except for fibrolamellar carcinoma. This rare type, often affecting women under 35 without preexisting liver disease, tends to have a better outlook.

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Accounting for 10% to 20% of liver cancers, these originate in the bile ducts within the liver. Although primarily focusing on hepatocellular carcinoma, treatments often overlap for cholangiocarcinomas.

Angiosarcoma and Hemangiosarcoma

These rare cancers develop in cells lining the liver’s blood vessels, often linked to chemical exposures such as vinyl chloride, thorium dioxide, arsenic, or hereditary conditions like hemochromatosis. They usually spread rapidly, making surgical removal difficult. Chemotherapy and radiation can slow progression, though treatment is challenging.

Hepatoblastoma

Primarily affecting children under four, hepatoblastoma resembles fetal liver cells. Successful treatment often involves surgery and chemotherapy, though prognosis worsens if the cancer spreads beyond the liver.

Secondary Liver Cancer

When cancer is discovered in the liver, it often originates elsewhere, termed secondary liver cancer. These metastatic tumors are named and treated based on their primary site. For instance, lung cancer that spreads to the liver is treated as lung cancer, not liver cancer. Secondary liver tumors are more common than primary in many Western countries.

Benign Liver Tumors

Although benign tumors don’t invade nearby tissues or metastasize, they can grow large enough to cause issues. Surgical removal can resolve them.

Hemangioma

The most frequent benign liver tumor stems from blood vessels, usually symptomless but sometimes requiring surgical intervention if bleeding occurs.

Hepatic Adenoma

These originate from hepatocytes and are typically asymptomatic but may cause abdominal pain or bleeding. Due to the risk of rupture and potential malignancy, surgical removal is often recommended. Factors increasing risk include use of certain medications like birth control pills and anabolic steroids, with tumors sometimes shrinking upon discontinuation of these drugs.

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia (FNH)

FNH consists of various cell types and is benign, though it may cause symptoms. Distinguishing FNH from malignant tumors can be challenging, leading to surgical removal for diagnostic clarity. Both hepatic adenomas and FNH are more prevalent in women.

Stages of Liver Cancer

When a liver cancer diagnosis is made, doctors determine the extent of cancer spread, known as staging. This process is crucial for assessing the cancer’s severity and planning the best treatment strategy. The stage also helps in understanding survival statistics.

Liver cancer stages range from I to IV, with lower numbers indicating less spread. A higher stage, like IV, means more significant spread. Despite individual differences, cancers at the same stage typically have similar treatment approaches and prognosis.

Determining the Stage

Several staging systems exist for liver cancer, but the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) TNM system is most commonly used in the U.S. It is based on:

– Tumor Size and Extent (T): Assessing the size, number of tumors, and their invasion into nearby structures.

– Lymph Node Involvement (N): Checking if cancer has reached nearby lymph nodes.

– Distant Metastasis (M): Determining if cancer has spread to distant organs like bones or lungs.

Staging Details

Each T, N, and M category is further detailed by numbers or letters, with higher numbers indicating more advanced cancer. This information is combined into stage grouping, leading to an overall stage classification.

– Stage IA: – A single tumor ≤2 cm not invading blood vessels.

– Stage IB: – A single tumor >2 cm without blood vessel invasion.

– Stage II: – A single tumor >2 cm with blood vessel invasion or multiple tumors ≤5 cm.

– Stage IIIA: – Multiple tumors, at least one >5 cm.

– Stage IIIB: – Tumor invasions into major liver veins.

– Stage IVA: – Tumor that has spread to nearby lymph nodes.

– Stage IVB: – Tumor that has metastasized to organs like the bones or lungs.

Other Staging Systems

Due to liver damage often accompanying liver cancer, multiple staging systems account for this complexity, such as:

– Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system

– Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) system

– Okuda system

These vary globally, with no universal standard. Staging systems like these consider liver function assessment, crucial for treatment decisions.

Child-Pugh Score

The Child-Pugh score assesses liver function, especially in cirrhosis, incorporating factors like:

– Blood bilirubin and albumin levels

– Prothrombin time

– Presence of abdominal fluid (ascites)

– Impact on brain function

Liver function is classified into three classes (A, B, C) based on normality or severity of abnormalities, impacting treatment suitability.

Liver Cancer Classification

Doctors often classify liver cancers based on resectability:

– Resectable or Transplantable Cancers: Can be fully removed surgically; typically early-stage cancers without significant liver damage.

– Unresectable Cancers: Cannot be completely removed due to size, spread, or proximity to vital structures.

– Inoperable Cancer with Local Disease: The patient’s health doesn’t permit surgery despite the cancer’s resectability potential.

– Advanced (Metastatic) Cancers: Spread to distant organs; generally not operable.

If you have questions about the stage of your cancer or the staging system used, discuss it with your doctor for clarity.

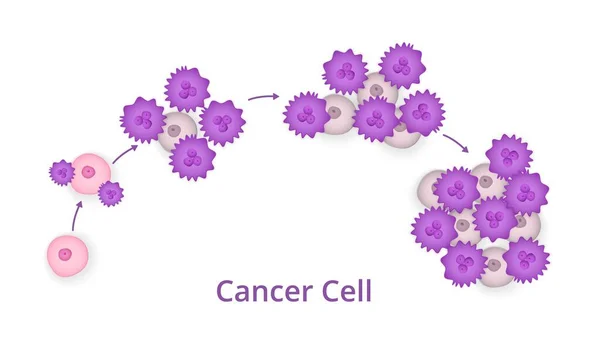

Causes of Liver Cancer

Liver cancer occurs when mutations develop in the DNA of liver cells. DNA contains the instructions that govern every cellular activity in the body. When these mutations alter the instructions, cells may grow uncontrollably, leading to the formation of a tumor composed of cancerous cells.

In some cases, liver cancer can be attributed to known factors like chronic hepatitis infections. However, it can also occur in individuals without any underlying conditions, where the cause remains unclear.

Risk Factors

Several factors can increase the risk of developing primary liver cancer:

– Chronic Hepatitis Infections: Long-term infections with hepatitis B (HBV) or hepatitis C (HCV) markedly elevate the risk.

– Cirrhosis: This irreversible liver scarring condition raises the likelihood of liver cancer.

– Inherited Liver Diseases: Conditions like hemochromatosis and Wilson’s disease can increase risk.

– Diabetes: Individuals with this condition face a higher risk of liver cancer.

– Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Fat buildup in the liver can heighten risk.

– Aflatoxin Exposure: These carcinogenic toxins from molds on poorly stored crops can contaminate food products.

– Excessive Alcohol Use: Long-term, heavy alcohol consumption can lead to irreversible liver damage, increasing cancer risk.

Prevention Strategies

Minimize Cirrhosis Risk

– Moderate Alcohol Consumption: If you drink, limit it to one drink per day for women and two for men.

– Maintain a Healthy Weight: Follow a balanced diet and engage in regular exercise to sustain a healthy body weight.

Prevent Hepatitis Infections

– Hepatitis B Vaccination: Vaccination can significantly reduce the risk of contracting HBV and is available for infants, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems.

– Hepatitis C Precautions: Although vaccines for hepatitis C are unavailable, you can lower the risk by:

– Knowing the health status of any sexual partners and using protection if necessary.

– Avoiding IV drug use. If unavoidable, use only sterile needles and avoid sharing.

– Choosing reputable shops for piercings or tattoos where strict sterilization procedures are followed.

Treat Hepatitis B or C Infections

Effective treatments are available for hepatitis B and C, which can lower the risk of liver cancer.

Liver Cancer Screening

Screening for liver cancer in the general population is not universally recommended due to a lack of evidence that it reduces mortality. However, individuals with increased risk factors, such as those with hepatitis B or C or cirrhosis, might consider screening. Discuss the benefits and potential drawbacks with your doctor to determine if screening, typically involving a blood test and abdominal ultrasound every six months, is appropriate for you.